The Naming of Mount Baker

Monday, April 30, 1792

[Vol.II, p.52-56]

The evening of the 29th brought us to an anchor in very thick rainy weather, about eight miles within the entrance on the southern shore of the supposed straits of De Fuca. The following morning, Monday the 30th, a gentle breeze

sprang up from the N. W. attended with clear and pleasant weather, which presented to our view this renowned inlet. Its southern shores

were seen to extend, by compass, from N. 83 W. to E; the former being the small island we had passed the preceding afternoon, which

lying about hald a mile from the main land, was about four miles distant from us: its northern shore extends from N. 68 W. to N. 73 E.; the

nearest point of it, distant about three leagues, bore N. 15 W.

We weighed anchor with a favorable wind, and steered to the east along

the southern shore, at the distance of about two miles, having an uninterrupted horizon between between east and N. 73 E. The shores on

each side the straits are of a moderate height; and the delightful serenity of the weather permitted our seeing this inlet to great advantage. The shores on the south side are composed of low sandy cliffs, falling perpendicularly on beaches of sand or stones. From the top of these eminences, the land appeared to take a further gentle moderate ascent, and was entirely covered with trees chiefly of the pine tribe, until the forest reached a range of high craggy mountains, which seemed to rise from the woodland country in a very abrupt

manner, with a few scattered trees on their steril sides, and their summits covered with snow. The northern shore did not appear quite so high: it rose more gradually from the sea-side to the tops of the mountains, which had the appearance of a compact range, infinitely more uniform, and much less covered with snow than those on the southern side.

Our latitude at noon was 48o 19'; longitude 236o 19'; and the variation of the compass 18o eastwardly. In this situation, the northern shore

extended by compass from N. 82 W. to N. 51 E. ; between the latter, and the eastern extremity of the southern shore, bearing N. 88 E., we

had still an unbounded horizon; whilst the island before mentioned, continuing to form the west extremity of the southern shore, bore S. 84

W. By these observations, which I have great reason to believe were correctly taken, the north promontory of Classet is situated in latitude

48o 23'; longitude 235o 38'. The smoothness of the sea, and clearness of the sky, enabled us to take several sets of lunar distances,

which gave the longitude to the eastward of the chronometer, and served to confirm our former observations, that it was gaining very

materially on the rate as settled at Otaheite. As the day advanced, the wind, which as well as the weather was delightfully pleasant,

accelerated our progress along the shore. This seemed to indicate a speedy, termination to the inlet; as high land now began to appear

just rising from that horizon, which, a few hours before, we had considered to be unlimited. Every new appearance, as we proceeded,

furnished new conjectures; the whole was not visibly connected; it might form a cluster of islands separated by, large arms of the sea, or

be united by land not sufficiently high to be yet discernable. About five in the afternoon, a long, low,

sandy point of land was observed

proiecting from the craggy shores into the sea, behind which was'seen the appearance of a well sheltered bay, and, a little to the S. E. of

it, an opening in the land, promising a safe and extensive port.

About this time a very high conspicuous craggy mountain

[Mount Baker],

bearing by

compass N. 50 E. presented itself, towering above the clouds as low

down as they allowed it to be visible, it was covered with snow; and

south of it, was a long ridge of very rugged snowy mountains

[Cascade Mountain Range],

much less elevated which seemed to stretch to a considerable distance.

As my intention was to anchor for the night under the low point, the necessary, signals were made to the Chatham; and at seven we

hauled round it, at the distance of about a mile. This was, however, to near, as we soon found ourselves in three fathoms water; but, on

steering about half a ale to the north, the depth increased to ten fathoms, and we rounded the shallow spit, which, though not very

conspicuous, is shewn by the tide causing a considerable rippling over it. Having turned up a little way into the bay, we anchored on a

bottom of soft sand and mud in 14 fathoms water. The low sandy point of land, which from its great resemblance to Dungeness in the

British channel, I called NEW DUNGENESS, bore by compass N. 41 W. about three

miles distant, from whence the low prejecting, land extends until it reaches a bluff cliff of a moderate height, bearing from us S. 60 W.

about a league distant. From this station the shores bore the same appearance as those we had passed

in the morning, composing one entire forest. The snowy mountains of the inland country were, however, neither so high nor so rugged, and

were further removed from the sea shore. The nearest parts bore by compass from us, south about half a league off; the apparent port S. 50 E. about two leagues; and the south point of an inlet, seemingly very capacious, S. 85 E.; with land appearing like an island,

moderately elevated, lying before its entrance, from S. 85 E.; to N. 87 E.; and the S. E. extremity of that which now appeared to be

southern shore, N. 71 E. From this direction round by the N and N.W. the high distant land formed, as already observed, like detached

islands, amongst which the lofty mountain, discovered in the afternoon by the third lieutenant, and in compliment to him called by me

MOUNT BAKER,

rose a very conspicuous object, bearing by compass N. 43 W.

apparently at a very remote distance.

The Cascade Range

Wednesday, May 2, 1792

[Vol.II, p.64-65]

A light pleasant breeze springing up, we weighed on Wednesday morning the 2d and steered for the port we had

discovered the preceding day, whose entrance about four leagues distant bore S. E. by E. The delightful serenity of the weather greatly

aided the beautiful scenery that was now presented; the surface of the sea was perfectly smooth, and the country before us exhibited

everything that bounteous nature could be expected to draw into one point of view. As we had no reason to imagine that this country had

ever been indebted for any of its decorations to the hand of man, I could not possibly believe that any uncultivated country had ever been

discovered exhibiting so rich a picture. The land which interrupted the horizon between the N. W. and the northern quarters, seemed, as

already mentioned, to be much broken; ftom whence its eastern extent round to the S. E. was bounded by

a ridge of snowy mountains,

[Cascade Mountain Range]

appearing to lie nearly in a north and south direction, on which mount Baker

[Mount Baker]

rose conspicuously; remarkable for its height, and the snowy

mountains

[Cascade Mountain Range]

that stretch from its base to the north and

South.

Between us and this snowy range, the land, which on the sea shore

terminated like that we had lately passed, in low perpendicular

cliffs, or on beaches of sand or stone, rose here in a very gentle ascent,

and was well covered with a variety of stately forest trees.

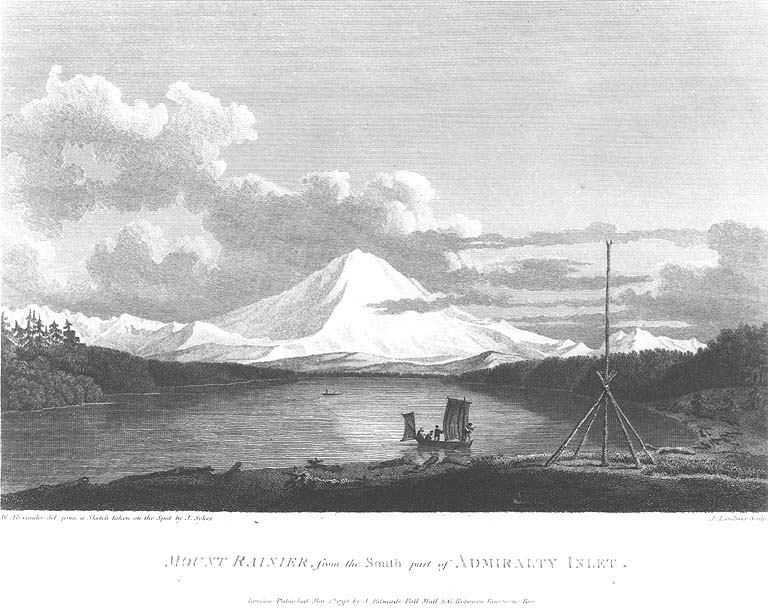

Spotting Mount Rainier

Monday, May 7, 1792

[Vol.II, p.72-75]

... about five o'clock on Monday morning the 7th, we took our departure for the purpose of becoming more intimately acquainted with the region

in which we had so very unexpectedly arrived. The day did not

promise to be very auspicious to the commencement of our examination.

That uninterrupted serenity of weather that we had experienced

the last seven days, seemed now to be materially changed;

the wind which, in the day-time, had constantly blown from

the N. W. with light southwardly airs, or calms, from sunset

until eight or ten o'clock in the forenoon, had now blown,

since the preceding evening, a moderate gale from the S. E.;

and, before we had proceeded a mile from the ship, brought

with it a very thick fog, through which we steered, keeping

the starboard, or continental shore, on board, trusting that

towards noon the fog would disperse itself and clear away.

On our arrival in port Discovery, we passed to the S. W.

of Protection island; another channel, equally as safe and

convenient, we now found to the S. E. of it. Having rowed

against a strong tide along the shore about two or three

leagues to the N. E. from the entrance of port Discovery, we

rounded a low projecting point, and though the fog prevented

our seeing about us, yet there was no doubt of our having entered

some other having entered some other harbour or arm in the inlet that took a southwardly direction. Here I proposed to wait until the weather should be more favorable, and in the mean time to haul the seine; which was done, along the beach to the southward, with little success.

Prosecuting our labours as fishermen along the beach, we were led near a point similar to that we had passed, and distant from it about

two miles; here the fog entirely dispersmiLy, afforded an opportunity of ascertaining its latitude to be 48o 7' 30", its longitude 237o 31 1/2'

A very spacious inlet now presented itself, whose N. E. point, in a line with its S. W. being the point from which we had last departed, bore

by compass N. 25 W. and seemed about a league asunder: mount Baker

[Mount Baker]

bore N. 26 E.; a steep bluff point opposite to us,

appearing to form the west point of another arm of this inlet, S. 87 E. about

four miles distant; the nearest eastern shore S. 5o E. about two miles;

and a very remarkable high round mountain, covered with snow,

apparently at the southern extremity of the distant range of

snowy mountains before noticed, bore S. 45 E.:

[Mount Rainier]

the shores of this inlet, like those in port Discovery, shoot out into several low, sandy, projecting points, the southernmost of which bore S. 9 E. distant about two leagues, where this branch of the inlet

seemed to terminate, or take some other direction. Here we dined, and having

taken the necessary angles, I directed Mr. Puget to sound

the mid-channel, and Mr. Johnstone to examine the larboard or eastern shore,

whilst I continued my, researches on the continental

shore, appointing the southernmost low point for our next rendezvous.

As we advanced, the country seemed gradually to improve in

beauty. The cleared spots were more numerous, and of larger extent;

and the remote lofty mountains covered with snow, reflected greater

luster on the fertile productions of the less elevated country.

On arriving near our place of rendezvous, an opening was seen, which gave

to the whole of the eastern shore under the examination of Mr. Johnstone,

the appearance of being an island. For this we steered, but

found it closed by a low sandy neck of land, about two hundred yards in width,

whose opposite shore was washed by an extensive salt lake, or more probably by an arm of the sea stretching to the S. E. and directing its main branch towards the high round snowy mountain we had discovered at noon

[Mount Rainier]

but where its entrance was situated we could not

determine though conjecture led to suppose it mould be

found round the bluff point of land we had observed from our dinner station.

In the western comer of this isthmus was situated a deserted Indian village, much in the same state of decay as, that which we had

examined at the head of port Discovery. No signs of any, inhabitants were discernible; nor did we visit it, it being expedient we should

hasten to our appointed station, as night was fast approaching, during which Mr. Johnstone did not join us; this led us to suppose he had

found some entrance into the above lake or inlet that had escaped my notice; and which afterwards proved to have been the cause of his

absence. Having determined the extent of this inlet, whose south extremity is situated in latitude 47o 59', longitude 237o 31'; at

day-break the next morning, Tuesday the 8th, we embarked in pursuit of the entrance into the lake or inlet that we had discovered the preceding evening.

The Naming of Mount Rainier

Tuesday, May 8, 1792

[Vol.II, p.72-75]

In most of my excursions I met with an indurated clay, much resembling fuller's-earth. The high steep cliff, forming the point of land we

were now upon, seemed to be prmcipally composed of this matter; which, on a more close examination, appeared to be a rich species of

the marrow stone, from whence it obtained the name of MARROWSTONE POINT. East of this cliff, the shore is extended about a quarter

of a mile by one of those sandy projecting points we had so frequentl met with. Here we dined, and had an

yxcellent view of this inlet, which appeared to be of no inextent. The eastern shore stretched by compass from N. 41 W. to S. 51 E.; the

south extremity of the 'western shore bore S. 26 E. ; and, between these latter bearings, the horizon was occupied by islands, or land

appearing much broken. The weather was serene and pleasant, and the country continued to exhibit, between us and the eastern snowy

range, the same luxuriant appearance. At its northern extremity, mount Baker

bore by compass N. 22 E.; the round snowy mountain, now

forming its southern extremmy, and which, after my friend Rear Admiral Rainier, I distinguished by the name Of

MOUNT RAINIER, bore N. [S.] 42 E.

Having finished all our business at this station,

the boats received the same directions as before; and having appointed the western. part

of some land appeanng like a long island, and bearing S. E. by S. four leagues distant, for our evening's rendezvous, we left

Marrow-Stone point with a pleasant grale, and every prospect of accomplishing our several tasks., The favourable breeze availed us but

little; for we had not advanced a league before we found the influence of so strong an ebb tide that, with all the exertions of our oars in

addition to our sails, we could scarcely make any progress ...

Spotting Mount St. Helens

Saturday, May 19, 1792

[Vol.II, p.117-121]

During the night, we had a gentle southerly breeze, attended by a fog which continued until nine o'clock on Saturday morning the 19th, when it was dispersed by a return of the N. W. wind, with which we pursued our route up the inlet; our progress was, however, soon retarded by the fore-topsail

yard-giving way in the slings; on examination it appeared to have been in a defective state some time. The spare fore-topsail yard was also very imperfect; which obliged us to get the spare main-topsail yard up in its room; and it was a very fortunate circumstance, that these defects were discovered in a country abounding with materials to which we could resort; having only to make our choice from amongst thousands of the finest spars the world produces.

To describe the beauties of this region, will, on some future occasion, be a very grateful task to the pen of a skilful panegyrist. The serenity of the climate, the innumerable pleasing landscapes, and the abundant fertility that unassisted nature puts forth, require only to be enriched by the industry of man with villages, mansions, cottages, and other buildings, to render it the most lovely country that can be imagined; whilst the labour of the inhabitants would be amply rewarded, into bounties which nature seems ready to bestow on cultivation.

About noon; we passed an inlet on the larboard or eastern shore, which seemed to stretch far to the northward; but, as it was out of the line of our intended pursuit of keeping the continental shore on board,

I continued our course up the main inlet, which now extended as far

as, from the deck, the eye could reach, though,

from the masthead, intervening land appeared, beyond which another high round

mountain covered with snow was discovered, apparently situated several leagues to the south of mount Rainier

[Mount Rainier], and bearing by compass

S. 22 E.

[Mount St. Helens]

This I considered as a further extension of the eastern snowy range

[Cascade Mountains];

but the intermediate mountains, connecting it with mount Rainier,

were not sufficiently high to be seen at that distance.

Having advanced about eight leagues from our last night's station,

we arrived off a projecting point of land, not formed I by a low sandy spit,

but rising abruptly in a low cliff about ten or twelve feet from the

water side. Its surface was a beautiful meadow covered with luxuriant herbage;

on its western extreme, bordering on the woods, was an Indian village, consisting, of temporary habitations, from whence several of the natives asembled to view the ship as we passed by; ...

Our situation being somewhat incommoded by the meeting of diffrent tides,

we moved nearer in, and anchored in the same depth, and on

the same bottom as before, very conveniently to the shore.

Our eastern view was now bounded by the range of snowy mountains

[Cascade Mountain Range]

from mount Baker

[Mount Baker],

bearing by compass north to

mount Rainier

[Mount Rainier],

bearing N. 54. E.

The new mountain

[Mount St. Helens]

was hid by the more elevated parts of

the low land; the intermediate snowy mountains in

various rugged and grotesque shapes, were seen just to rear their heads above the lofty pine trees, which appearing to

compose one uninterrupted forest, between us and the snowy

range, presented a most pleasing landscape; nor was our western destitute of similar diversification. ...

In Puget Sound

Saturday, May 26, 1792

[Vol.II, p.133-135]

On Saturday morning the 26th, accompanied by Mr. Baker in the yawl,

and favored by pleasant weather and a fine

northwardly gale, we departed, and made considerable progress.

Leaving to the right the opening which had been the object of Mr. Puget

and Mr. Whidbey's expedition, we directed our route along the

western shore of the main inlet, which is about a league in width; and as

we proceeded the smoke of several fires were seen on its eastern shore.

When about four leagues on a southwardly direction from the

ships, we found the course of the inlet take a south-westerly inclination,

which we pursued about six miles with some little increase of

width. Towards noon we landed on a point on the eastern shore,

whose latitude I observed to be 47o 21', round which we flattered

ourselves we should find the inlet take an extensive eastwardly course.

This conjecture was supported by

the appearance of a very abrupt

division in the snowy range of mountains

[Cascade Mountain Range]

immediately to the south of

mount Rainier

[Mount Rainier], which was very conspicuous from the ship, and the

main arm of the inlet appeanng to stretch in that direction

from the point we were then upon. We here dined, and although our repast was

soon concluded, the delay was irksome, as we were excessively

anxious to ascertain the truth, of which we were not long held in

suspense. For having passed round the point, we found the inlet

to terminate here in an extensive circular compact bay, whose waters

washed the base of mount Rainier,

though its elevated summit was yet at a very considerable

distance from the shore, with which it was

connected by several ridges of hills rising towards it

with gradual ascent and much regularity. The forest trees,

and the several shades of verdure that covered the hills, gradually decreasing in point of beauty, until they became invisible; when the

perpetual clothing of snow commenced, which seemed to form a horizontal line from north to south along this range of rugged mountains,

from whose summit mount Rainier rose conspicuously, and seemed as much

elevned above them as they were above the level of the sea; the

whole producing a most, grand, picturesque effect.

The lower mountains as they descended to the right and left, became gradually relieved of,

their frigid garment; and as they, approached the fertile woodland

region that binds the, shores of this inlet in every direction,,

Produced a pleasing variety. We now proceeded to the N. W. in which

direction the inlet from hence extended, and afforded us some

reason to believe that it communicated with that under the survey of our

other party. This opinion was further corroborated by a few Indians,

who had in a very civil manner accompanied us some time, and who

gave us to understand that in the north western direction this inlet

was very wide and extensive; this they impressed before we quitted our

dinner station, by opening their arms, and making other signs that we

should be led a long way by usuing that route; whereas, by bending

their arm, or spreading , out their hand, and pointing to the space

contained in the curveor the arm, or between the fore-finaer and thumb,

that we should find our progress I soon stopped in the direction which led towards mount Rainier. ...

Spotting Mount St. Helens and Mount Adams ???

Thursday, June 7, 1792

[Vol.II, p.174-176]

On reflecting that the summer was now fast advancing, and that the slow progress of the vessels occasioned too much delay, I

determined, rather than lose the advantages which the prevailing favorable weather now afforded Or boat expeditions, to dispatch Mr.

Puget in the launch, and, Mr. Whidbey in the cutter, with a week's provisions, in order that the shores should be immediately explored to

the next intended station of the vessels, whither they would proceed as soon as circumstances would allow. In this arrangement I was well aware, it could not be considered judicious to part with our launch, whilst the ship remained in a transitory unfixed state in this unknown and dangerous navigation; yet she was so essentially necessary to the protection of our detached

parties, that I resolved to encounter some few difficulties on board, rather than suffer the delay, or lose so valuable an opportunity for the prosecution of the survey. In directing this, orders were given not to examine any opertings to the northward, beyond Strawberry bay, but to determine the boundaries of the continental shore leading to the north and eastward, as far as might be practicable to its parallel, whither they were to resort after performing the task assigned. On this service they departed, and directed their course for the first opening on the eastern shore about 3 or 4 leagues distant, bearing by compass from the ship N. by E.

Having repaired to the low sandy island already noticed, for the purpose of taking some angles, I found some rocks lying on its western side nearly three quarters of a mile from its shores; and that the eastern part of it was formed by a very narrow low spit of land, over which the tide nearly flowed. Its situation is in latitude 48o 24', longitude 237o 26 1/2 '.

Amongst the various bearings that it became necessary to take here, were those of the two remarkably high snowy mountains so frequently

mentioned

[Mount Baker and Mount Rainier].

Mount Baker

bore N. 63 E.;

mount Rainier

S. 27 E.;

and from a variety of observations purposely made for fixing

their respective situations, it appeared that

mount Baker

was in latitude 48o 39', longitude 238o 20', and

mount Rainier in

latitude 47o 3', longitude 238o 21'.

To the southward of these were now seen two other very lofty, round, snowy mountains, lying apparently in the same north and south direction, or nearly so; but we were unable to ascertain their positive situation.

[Mount St. Helens and Mount Adams ???]

The summits of these were visible only at two or three stations in the southern parts of Admiralty inlet; they appeared to be covered

with perpetual snow as low down as we were enabled to see, and seemed as if they rose from an extensive plain of low country.

Comments on the Cascade Range

Thursday, June 7, 1792 - Continued

[Vol.II, p.176-177]

When due attention is paid to

the range of snowy mountains that stretch to the southward

[Cascade Mountain Range]

from the base of mount Rainier, a

probability arises of the same chain being continued, so as to connect the whole in one barrier along the coast, at uncertain distances from its shores; although intervals may exist in the ridge where the mountains may not be sufficiently elevated to have been discernable from our several stations. The like effect is produced by the two former mountains, whose immense height permitted their appearing very conspicuously, long before we approached sufficiently near to distinguish the intermediate range of rugged mountains that connect them, and from whose summits their bases originate.

Naming Mount St. Helens

Saturday, October 20, 1792

[Vol.II, p.399]

The clearness of the atmosphere enabled us to see the high round snowy mountains, noticed when in the southern parts of Admiralty inlet, to the southward of mount Rainier; from this station it bore by compass N. 77 E. and, like mount Rainier, seemed covered with perpetual snow, as low down as the intervening country permitted it to seen. This I have distinguished by the name of MOUNT ST. HELENS, in honor of his Britannic Majesty's ambassador at the court of Madrid. It is situated in latitude 46o 9' and in longitude 238o 4', according to our observations.

Mount St. Helens

Monday, October 29, 1792

[Vol.III, p.102-103]

The next morning

(October 29)

they again proceeded up

the river and had a

distant view of mount St. Helens

lying N. 42 E.

In sounding across the river, whose width was there

about a quarter of a mile, from three to twelve

fathoms water was found. Owing to the rapidity of

the stream against them they were under the necessity

of stopping to dine at not

more than four or five miles from their resting

place; there it was low water at noon, and though

the water of the river evidently rose afterwards,

yet the stream continued to run

rapidly down. The greatest perpendicular rise and

fall appeared to be about three feet. In this

situation the latitude was observed to be

45o 41', longitude 237o, 20'; when mount St. Helens

was seen lying from hence N. 38 E. our distance from

point Warrior

[western end of Sauvie Island]

being about eight miles.

Spotting Mount Hood

Monday, October 29, 1792 - Continued

[Vol.III, p.103-104]

At one o'clock they quitted their dinner station,

and after rowing about five miles still in the

direction of the river S. 5 E., they passed on the

western side of a small river leading to

the south-westward; and half a mile further

on the same shore came to a larger one,

that took a more southerly course.

In the entrance of the latter, about a quarter of a mile in width,

are two small woody islets; the soundings across it from two to five fathoms. The ajacent country, extending from its banks, presented

a most beautiful appearance. This river Mr. Broughton

distinguished by the name of

RIVER MUNNINGS

[Willamette River]. --

Its southern point of entrance,

situated in latitude 45o 39',

longitude 237o 21', commanded a

most delightful prospect of the surrounding

region, and obtained the name of

Belle Vue Point

[eastern end of Sauvie Island];

from whence the

branch of the river, at least that which

was so considered, took a direction about S. 57 E. for a league and a

half.

A very high, snowy mountain

now appeared

rising beautifully conspicuous in the

midst of an extensive tract of low, or

moderately elevated, land, lying S 67 E., and seemed to

announce a termination to the river.

[Mount Hood]

The Naming of Mount Hood

Tuesday, October 30, 1792

[Vol.III, p.105-108]

The wind blew fresh from the eastward, which, with the stream against

them, rendered their journey very slow and tedious. They passed a small

rocky opening that had a rock in its centre, about twelve feet above the

surface of the water; on this were lodged several large trees that must

have been left there by an unusually high tide.

From hence a large river

bore S.5 E., wich was afterwards seen to take a south-westwardly direction,

and was named

BARING'S RIVER

[Sandy River];

between it and the shoal creek is

another opening; and here that in which they had reseted stretched to the

E. N. E., and had several small rocks in it. Into this creek the friendly

old chief who had attended them went to procure some salmon, and they pursued their way against

the stream, which was now become so rapid that they were able to make but

little progress. At half past two they stopped on the northern shore to

dine, opposite the entrance of Baring's River.

Ten canoes with the natives

now attended them, and their friendly old chief soon returned and brought

them an abundance of very fine salmon. He had gone through the rocky

passage, and had returned above the the party, making the land on which

they were at dinner an island. This was afterwards found to be about

three miles long, and after the lieutenant of the Chatham, was named

JOHNSTONE'S ISLAND

[Lady Island].

The west point of

Baring's River is situated

in latitude 45o 28' longitude 237o 41'; from

whence the main branch takes rather an irregular course, about N. 82 E.; it

is near half a mile wide, and in crossing it the depth was from six to

three fathoms. The southern shore is low and woody, and contracts the

river by means of a low sandy flat that extends from it, on which were

lodged several large dead trees. The best passage is close to

Johnstone's island;

this has a rocky, bold shore, but Mr. Broughton pursued the

channel on the opposite side, where he met with some scattered rocks;

these however admitted of a good passage between them and the main land;

along which he continued until towards evening, making little progress

against the stream. "Having now passed the sand bank," says Mr. Broughton,

"I landed for the purpose of taking our last bearings; a sandy point on

the opposite shore

[Point Vancouver, upstream of Washougal, Washington]

bore S. 80 E., distant about 2 miles; this point

terminating our view of the river, I named it after Captain Vancouver; it

is situated in latitude 45o 27', longitude 237o 50'."

The same remarkable mountain that had been seen from

Belle Vue point, again presented itself, bearing at this

station S. 67 E.; and though the party were now nearer

to it by seven leagues, yet its lofty summit was scarcely

more distinct across the intervening land which was

more than moderately elevated. Mr. Broughton honored it

with Lord Hood's name; its appearance was magnificent;

and it was clothed in snow from its summit, as low down

as the high land, by which it was intercepted, permitted it to be visible. Mr. Broughton lamented that he could not

acquire sufficient authority to ascertain its

positive situation, but imagined it could not be less than 20

leagues from their then station.

|